The facts: What you need to know about the Syria crisis

In early December 2024, with the collapse of the Syrian government, displaced communities are at a crucial turning point after 13 years of conflict. More than 5.4 million Syrians had been forced out of the country, and hundreds of thousands may soon return. “It is imperative to prioritize the restoration of—and dignified access to—essential services for the millions of internally displaced people and refugees planning to return,” says Mathieu Rouquette, Mercy Corps Country Director for Syria.

Read more about the situation: “A new chapter begins for communities in Syria"

The Syrian conflict has created one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time.

Since 2011, over half of Syria’s pre-war population of 22 million has been forced to flee their homes in search of safety and opportunity, many of them more than once. Families still living in Syria are struggling to survive and meet their basic needs: 13.4 million people need humanitarian assistance, including 6.7 million who are internally displaced.

As the crisis enters its tenth year with no end in sight, millions of Syrians continue to suffer while grappling with the added threat of COVID‑19. Every day, a lack of food and water and limited access to health services put millions of lives at risk.

In Northwest Syria, one of the most fragile regions of the country, basic necessities have become particularly sparse, and the delivery of critical aid across borders has become increasingly challenging. Meanwhile, brutal winter conditions and rising COVID‑19 cases threaten the survival of children and families who have already lost so much.

As complex as the crisis has become, one fact remains simple: millions of Syrians need our help. According to the U.N., $3.8 billion was required to meet the urgent needs of the most vulnerable Syrians in 2020 — but just over half of that has been received.

You can help. The more you know about the crisis, the more we can do together to help those in need. The lifesaving work we do, helping people to survive through crisis and build better lives, is only possible with your knowledge and support.

So take a few minutes to understand the magnitude of this crisis, learn the facts behind the figures and find out how you can help.

- When did the crisis in Syria start?

- How long has the crisis been going on?

- How has the war affected Syrians?

- What effect is COVID‑19 having on the Syria crisis?

- What are the challenges for organisations like Mercy Corps?

- What can we do to help the people of Syria?

- How many Syrian refugees are there?

- Where are Syrians fleeing to?

- Do all refugees live in camps?

- What conditions are Syrian refugees facing outside camps?

- How many Syrian refugees are children?

When did the crisis in Syria start?

Anti-government demonstrations began in March of 2011, as part of the Arab Spring. But the peaceful protests quickly escalated after the government's violent crackdown, and armed opposition groups began fighting back.

By July of 2011, army defectors had loosely organised the Free Syrian Army and many civilian Syrians took up arms to join the opposition. Now, a decade later, divisions between armed groups and between ethnic groups continue to complicate the politics of the conflict.

How long has the crisis been going on?

The Syria crisis is now entering into its second decade. The past ten years represent as deadly and devastating a decade as any one country has experienced in recent memory, and can be defined by a collection of key moments and milestones:

- March 2011: Anti-government demonstrations begin as part of the Arab Spring.

- July 2011: The conflict is declared a civil war as violence becomes widespread.

- July 2012: Zaatari Refugee Camp is opened in Jordan and hosts 120,000 refugees in its first year.

- March 2013: The number of registered Syrian refugees reaches 1 million.

- July 2014: The U.N. Security Council adopts a resolution authorizing the delivery of cross-border aid into Syria.

- September 2015: Conflict intensifies as outside parties become involved. A large number of Syrian refugees arrive in Europe, and Mercy Corps expands its response.

- July 2016: The battle for Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, begins and lasts through August, displacing thousands.

- July 2017: The number of registered Syrian refugees surpasses 5 million.

- December 2019: Renewed airstrikes and bombings begin in Northwest Syria and force 961,000 people to flee over the span of three months — the largest displacement since the beginning of the conflict.

- July 2020: The cross-border resolution is further curtailed, resulting in the closure of one of two remaining official border crossings used to deliver humanitarian aid.

- July 2020: The first case of COVID‑19 is documented in Northern Syria.

How has the war affected Syrians?

As Syria makes headlines and policymakers in Washington, D.C., at the United Nations and around the world negotiate the fate of the country’s future, those caught in the crossfire of the conflict are often forgotten or overlooked: millions of innocent civilians and families enduring an unimaginable scale of suffering. The Syrian people have lived through years of violence, displacement and loss.

The war has killed hundreds of thousands of people in the ten years since it began. Crowded cities have been destroyed and horrific human rights violations are widespread. Millions of families have been forced to flee home in search of safety or opportunity.

It’s estimated that 6.7 million people are internally displaced inside Syria — more than half of them are women and children. When you also consider refugees, more than two-thirds of the country’s pre-war population of 22 million is in need of urgent humanitarian assistance, whether they still remain in the country or have escaped across the borders.

Today, COVID‑19 restrictions, the collapse of the Syrian pound and the displacement of millions of people have led to an unprecedented number of families in Syria who are no longer able to put food on the table or make enough money to afford basic necessities. Eight in 10 people are living below the poverty line, with limited access to education and job opportunities, and a record 12.4 million people are going to sleep hungry every night — around 60% of the entire Syrian population.

What effect is COVID-19 having on the Syria crisis?

The pandemic has presented challenges to each and every country around the world. For Syria, the magnitude of these challenges may be just beginning to be felt.

In the northwest, the first cases of COVID‑19 were confirmed in July of 2020. Home to more than 4 million people, many of whom have been displaced multiple times, Idlib and northern Aleppo governorates are now facing the catastrophic impacts of the virus. Many families live in squalid makeshift overcrowded camps or sleep out in the open. Water is scarce here, and the health and civilian infrastructures are decimated. According to the World Health Organization, only half of health facilities in this region are still open and operational.

In the northeast, the first cases of COVID‑19 were confirmed in April of 2020, and concerns over a lack of preparedness remain high. Lack of COVID‑19 testing capacity, chronically understocked health facilities and inefficient water services continue to be the daily reality. Like in the northwest, taking measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus is especially difficult in the many overcrowded camps and informal settlements across the region.

In government-held areas, as in neighbouring countries hosting refugees, Syrians are facing the reality that the threat of COVID‑19, the inability to work and the spiraling economic decline in the region is making their situation harder than ever.

Our teams are currently working to reduce the risk of spread by sharing up-to-date information on COVID‑19 alongside the delivery of basic essentials to people fleeing conflict. In addition to supplying our water and sanitation programming to conflict-affected areas in Northeast Syria, we’re also boosting our messaging about hygiene, COVID‑19, stigmatisation that sometimes happens with infection and how families can access local systems.

In Northwest Syria, our team worked quickly to prepare for COVID‑19 outbreaks in camps, running water delivery simulations to ensure the process would run smoothly in the event of a full outbreak.

From Kieren, our Country Director: “Since March [2020], Mercy Corps teams have increased the amount of soap and water we provide to each family, and have delivered additional water tanks to improve safe water storage. We are also distributing COVID‑19 flyers in camps and educating communities on the risks and how to stay safe.

“Too often, though, families tell us that they aren't able to take the necessary steps to protect themselves and their families. In displacement camps or mass shelters such as vacant mosques and schools, with the health infrastructure reduced to rubble around them, the odds are stacked against them.”

Now, as Syria begins receiving its first COVID‑19 vaccines, we must ensure the vaccine reaches the most vulnerable across the country, and that the effort does not interfere with the delivery of other critical lifesaving aid.

What are the challenges for organisations like Mercy Corps?

With no lasting peace in sight, Mercy Corps and other humanitarian organisations are struggling just to keep up with rapidly growing needs. U.N. appeals have been significantly underfunded every single year since the start of the Syrian crisis.

According to the U.N., $6 billion was required in 2020 to provide emergency support and stabilization to families throughout the region — but less than half of that was received.

To make matters more complicated, the U.N. Security Council approved a resolution on cross-border aid to the northwest on July 11, 2020 authorizing only limited access compared to years past. The decision allowed just one border crossing to remain open to deliver critical relief, and resulted in the closure of a crossing that 1.3 million people in northern Aleppo had relied on for survival. Every month, 2.4 million people in the region depend on cross-border humanitarian assistance.

The reduction in access and the volatility of the conflict have made the delivery of immediate aid — and longer-term development work— an ongoing challenge for organisations like Mercy Corps. Navigating around the crisis and reaching those in need with uninterrupted, lifesaving aid requires innovative solutions. With so many unknowns and uncertainties, our team members are working to help community members to be able to continue to provide support, with or without our presence on the ground.

Read our NGO joint statement on the impacts of limited access

What can we do to help the people of Syria?

Mercy Corps is working hard to relieve the intense suffering of civilians inside Syria, as well as that of refugees who sought safety in neighbouring countries. Today, our team members are helping hundreds of thousands of people affected by the crisis and doing all we can to stop the spread of COVID‑19.

We are delivering food and clean water, restoring sanitation systems, improving shelters and providing families with clothing, mattresses and other household essentials. We are helping children cope with extreme stress and leading constructive activities to nurture their healthy development, while helping host communities and refugees work together to mitigate tensions and find solutions to limited resources. We are also supporting livelihood development through the distribution of items like seeds and tools and facilitation of cash grants and business courses.

Since March 2020, this assistance has reached more than 1.6 million people across Syria.

We’ve worked in the region for 20 years and are committed to helping Syrians and the countries hosting them for as long as it takes.

How many Syrian refugees are there?

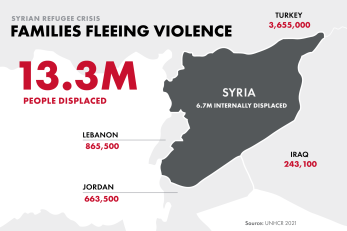

More than 13.3 million Syrians have been displaced from their homes since 2011 — enough people to fill roughly 245 Yankee Stadiums. This includes about 5.6 million refugees who have been forced to seek safety in neighbouring countries, out of a total of 6.6 million Syrian refugees worldwide — more than one-fourth of the world’s total refugee population.

Every year of the conflict has seen an exponential growth in refugees. In July 2012, there were 100,000 refugees. One year later, there were 1.5 million. That tripled by the end of 2015.

Today there are 5.6 million Syrians scattered throughout the region, making them the world's largest refugee population under the United Nations' mandate. It's the worst exodus since the Rwandan genocide 27 years ago.

Where are Syrians fleeing to?

More than 6.7 million people have fled their homes and remain displaced within Syria. They live in informal settlements, crowded in with extended family or sheltering in damaged or abandoned buildings. Some people survived the horrors of multiple displacements, besiegement, hunger and disease and fled to areas where they thought they would be safe, only to find themselves caught up in the crossfire once again. Nearly 40% of internally displaced families have been displaced more than three times over the course of the past decade.

Around 6.6 million Syrians have left the country entirely — the majority seeking refuge in neighbouring countries. More than 1.5 million Syrian refugees are living in Jordan and Lebanon, where Mercy Corps has been addressing their needs since 2012. In the region’s two smallest countries, weak infrastructure and limited resources are nearing a breaking point under the strain.

READ: Building strength within a community of Syrian refugees ▸

Nearly 3.7 million Syrian refugees have fled across the border into Turkey, overwhelming urban host communities and creating new cultural tensions.

Do all refugees live in camps?

The short answer: no. Most Syrian refugee families are struggling to settle in unfamiliar urban communities or have been forced into informal rural environments. They seek shelter in unfinished buildings, sometimes without proper kitchens or bathrooms, or stay in public buildings like schools or mosques. Others stay with relatives, sometimes even strangers, who welcome them in to their homes.

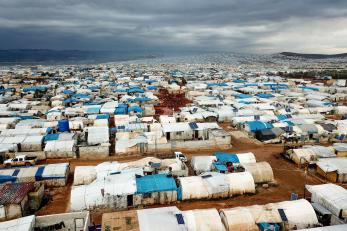

Only about 8% of Syrian refugees live in camps. Jordan’s Zaatari, the first official refugee camp that opened in July 2012, gets the most news coverage because it is the destination for newly-arrived refugees. It is also the most concentrated settlement of refugees: approximately 78,400 Syrians live in Zaatari, making it one of the country’s largest cities.

The formerly barren desert is crowded with acres of white tents, makeshift shops line a “main street” and sports fields and schools are available for children.

Azraq, a camp opened in April 2014, is carefully designed to provide a sense of community and security, with steel caravans instead of tents, a camp supermarket and organised "streets" and "villages."

See what refugees brought with them from home ▸

Because Jordan’s camps are run by the government and the U.N. — with many partner organisations like Mercy Corps coordinating services — they offer more structure and support. But many families feel trapped, crowded and even farther from any sense of home, so they seek shelter in nearby towns.

READ: One family's story in crowded Lebanon ▸

Iraq has set up a few camps to house the influx of refugees who arrived in 2013, but the majority of families are living in urban areas. And in Lebanon, the government has no official camps for refugees, so families establish makeshift camps or find shelter in derelict, abandoned buildings. In Turkey, the majority of refugees are trying to survive and find work, despite the language barrier, in urban communities.

What conditions are Syrian refugees facing outside camps?

Some Syrians know people in neighboring countries who they can stay with. But many host families were already struggling on meager incomes and do not have the room or finances to help as the crisis drags on.

Refugees find shelter wherever they can. Our teams have seen families living in rooms with no heat or running water, in abandoned chicken coops and in storage sheds.

See photos: 8 important things Syrians have lost to war ▸

Refugees often land in host countries without all their identification, which has either been destroyed or left behind. Without the right documents in host countries, refugees can be evicted from housing, be unable to access medical care, education or most often, just be afraid to leave their homes. Without these documents, we see many refugees resort to negative coping strategies, including child labor, early marriage and engagement in unsafe work.

The lack of clean water and sanitation in crowded, makeshift settlements is an urgent concern. Diseases like COVID‑19 can easily spread — even more life-threatening without enough medical services — and every year, freezing temperatures, heavy winds, rain and flooding threaten the lives of families who have already lost so much.

MORE: Winter in Syria, from a voice on the ground ▸

The youngest refugees face an uncertain future. Some schools have been able to divide the school day into two shifts and make room for more Syrian students. But there is simply not enough space for all the children, and many families cannot afford the transportation to get their kids to school.

How many Syrian refugees are children?

According to the U.N., almost half of all Syrian refugees — more than 2.5 million — are under the age of 18. Most have been out of school for months, if not years. More than 34,000 school buses would be needed to drive every young refugee to school.

The youngest are confused and scared by their experiences, lacking the sense of safety and home they need. The older children are forced to grow up too fast, needing to find work and take care of their family in desperate circumstances.

One demographic that is largely overlooked is adolescents. Through Mercy Corps’ extensive work in and around Syria, we continuously witness young adults and adolescents in crisis.

LEARN MORE: Unlocking a future for Syria's youth ▸

The consequence of forgetting the unique needs of this next generation will be steep: they risk becoming adults who are ill-equipped to mend torn social fabric and rebuild broken economies. Investing in adolescents now will yield dividends for decades to come for the peace and productivity so desperately needed in Syria and the region.