Youth unemployment: a global crisis

Over the next decade, the World Bank estimates one billion young people—a majority living in the countries Mercy Corps operates—will try to enter the job market, but less than half of them will find formal jobs. This will leave the majority of young people, many in minority and marginalised groups, unemployed or experiencing working poverty. The predicted rise in economic inequality and inadequate job opportunities has the potential to negatively impact a generation of young people around the world.

Learn more about global youth unemployment and what Mercy Corps is doing to help:

- What is youth unemployment?

- Why is youth unemployment a problem in the long term?

- What are youth unemployment rates around the world?

- Why is youth unemployment so high?

- What isn’t included in the youth unemployment rate?

- How is COVID‑19 affecting youth unemployment?

- Why is Mercy Corps working to solve the youth unemployment crisis?

- What is Mercy Corps doing to solve the youth unemployment crisis?

What is youth unemployment?

The term “youth unemployment” is exactly what its name implies: it results when young people – defined by the United Nations as 15-24 year-olds – are looking for jobs but can’t find them. While unemployment itself is a problem – especially in the wake of COVID‑19 – youth unemployment is quickly becoming a global crisis.

Youth is a concept that’s been widely debated, some people contending youth is merely a transition from childhood to adulthood, while others consider it a life stage that should be recognised for having its own set of complex issues and experiences, not the least of which is rapid socioeconomic change. No matter one’s views on the concept of youth, the situation known as youth unemployment is one that should concern us all.

Why is youth unemployment a problem in the long term?

Having a significant amount of young people out of work can negatively impact a community’s economic growth and development. If left unchecked, youth unemployment can have serious social repercussions because unemployed youth tend to feel left out, leading to social exclusion, anxiety and a lack of hope for the future. Given that almost 90% of all young people live in low-income nations, not feeling that a better life is possible can result in millions of young people floundering in poverty and frustration – bringing fragile nations down with them.

Looking at areas like Africa where there are nearly 200 million people between the ages of 15 and 24 (a number that’s expected to double by 2045), it’s easy to see that skyrocketing youth unemployment rates will have a serious impact if not addressed.

With more than 64 million unemployed youth worldwide and 145 million young workers living in poverty, youth employment remains a global challenge.

‑International Labor Organization, a specialised agency of the United Nations

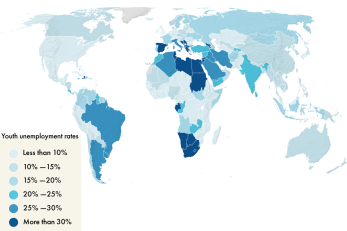

What are youth unemployment rates around the world?

Around the world, unemployment affects 67.6 million young people. While the global youth unemployment rate currently stands at 13.6%, the number varies drastically by region. Youth unemployment is highest in Northern Africa at an alarming rate of 30%, or more than twice the global rate. Even sub-Saharan Africa and Northern America – sub-regions with low unemployment probability – faced youth unemployment rates of almost 9% in 2019. These numbers show that there is a need to help young people enter into, and remain in, employment. The ongoing pandemic and resulting global economic challenges further complicate this need.

Currently the countries with the highest rates of youth unemployment are:

- Gabon: 36%

- Tunisia: 36.3%

- French Polynesia: 36.9%

- Botswana: 37.3%

- N. Macedonia: 39.1%

- Namibia: 39.5%

- French Guiana: 39.6%

- Bosnia: 39.7%

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines: 41.7%

- West Bank and Gaza: 42%

Why is youth unemployment so high?

According to a 2020 report from the International Labor Organization, a specialised agency of the United Nations, the global youth unemployment rate stands at 13.6%. The contributing factors to this high rate of global youth unemployment are largely due to the lack of job opportunities but also include barriers to entering the labor market, like limited work experience and the increasing size of the population itself – worldwide, there are approximately 1.3 billion young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

In regions like Africa, young people make up more than one fifth of the population and 95% of their work is considered informal. By definition, this means work that’s without legal or social protections. In practice, this typically means work that comes with low pay, erratic hours, uncertain employment status, and hazardous working conditions. In the first month of the COVID‑19 crisis, it’s been estimated that the income of informal workers like these dropped by 81%. Without alternate sources of income, these workers and their families will have no way to survive.

In places like Guatemala City, many young people run into barriers to employment they can’t escape. They can’t rise above the challenges of poverty and instability without opportunities – education or a good job – and they can’t access opportunity without the income or safety to pursue it. Young people living in red zones — neighborhoods known for being hot spots of drug- and gang-related violence – face even more dismal prospects based on employers’ perceptions that they are untrustworthy because of their address. It’s barriers like these that can keep young people from seeking opportunities to advance their futures, or even believing that those opportunities exist.

What isn’t included in the youth unemployment rate?

To be considered unemployed, one must be jobless, actively seeking work and available to take a job. So while there are approximately 41 million young people who make up the “potential labor force” not all of them are considered unemployed. Many are available for work but not actively seeking a job – often a result of discouragement.

This group of young people, combined with unemployed youth makes up a group commonly referred to as NEET – “not in employment, education or training.” This means they are not gaining experience in the labor market, not receiving an income from work, and not enhancing their education and skills. Globally, one in five young people, or 267 million, have NEET status.

While some of them may be contributing to the economy through unpaid work (which is particularly true of young women) one thing remains true for all of these young people: their full potential is not being realised. What’s more, all of these things – being unemployed, taking unpaid work, or being discouraged from working – in the early stages of a young person’s career can lead to a number of scarring effects, including lower employment and earning potential later in life.

Another group of young people not included in youth unemployment rates are those who are underemployed. In poor communities, people can’t afford to be unemployed, so they take any work they can get – resulting in underemployment, vulnerable employment and working poverty. While these people are not considered unemployed, they’re often more likely to suffer from poverty than many of their unemployed peers.

How is COVID‑19 affecting youth unemployment?

In times of crises, young people tend to be among the first to lose their jobs. With so many in the informal economy, and working in areas like tourism, transportation, and hospitality, where telework is not an option, young people are being especially hard hit by COVID‑19.

A report by the Africa Union estimates that due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, “nearly 20 million jobs, both in the formal and informal sectors, are threatened with destruction”. The resulting potential for social unrest in Africa is largely due to the disproportionately-affected youth demographic, whose level of unemployment is twice that of older adults and who make up the majority of the population.

In other areas of the world, COVID‑19’s impact on access to education and employment is setting an entire generation up for a potentially devastating employment trajectory. Being unemployed at a young age can have long-lasting, negative effects in terms of career paths and future earnings. Young people with a history of unemployment face fewer career development opportunities, lower wage levels, poorer prospects for better jobs, and ultimately lower pensions.

Young people also tend to have less money saved for emergencies, putting those living in economically vulnerable households at an increased risk of falling below the poverty line within 3 months, should their income suddenly stop or decline as a result of the pandemic. With an estimated 126 million young workers already living in extreme and moderate poverty worldwide pre-pandemic, the potential effects of COVID‑19 are almost unimaginable.

Why is Mercy Corps working to solve the youth unemployment crisis?

Today, our world is younger than ever before. The median age in the countries where we work tells an important story: Niger, 15 years; Mali, 16 years; Gaza, 18 years; Guatemala, 21 years; and Ethiopia, 17.6 years. Dozens of other countries are experiencing similar demographic trends. Partnering with young people is one way we can help them secure a brighter future for themselves and their families.

Why focus on youth employment? Employment, entrepreneurship and other income-generating opportunities often provide more than economic benefits – they provide youth with a purpose and a sense of status and belonging. Not to mention that the choices young people make today – which are influenced by the people and events around them – contribute to the possibility for peace, stability and progress in their communities and some of the world’s most fragile places.

A young person’s entry into the labor market has life-long implications for their career opportunities and maturation. Yet, almost half of all young people in the labor force are either working but poor or are unemployed. We have the unique ability to work with these young people to address the specific problems they’re facing. We can help them connect to new clients and opportunities, get access to career counseling, strengthen their capacity by supporting technical training and education systems; and help them access their first jobs through apprenticeships and internships.

What is Mercy Corps doing to solve the youth unemployment crisis?

We take a market systems approach, where we address root causes of youth unemployment rather than its symptoms. By building up the ecosystems around youth work, we ensure that our programmes have a lasting effect — even long after they have ended.

With all of our youth focused programmes, we do one thing differently than most organisations – we co-design with young people to be real partners in change. Youth have long been a neglected, underserved and misunderstood population. Displacement and conflict only increase their risk, invisibility and isolation. The result is that many aid programmes are blind to the barriers young people face. Moreover, little access to vital services further erodes their mental and physical health, severely limits the areas where they feel safe, and has a negative impact on their development.

Mercy Corps places adolescents in the front – as leaders – to be partners in the change they want to see. We design with them, not for them. Young people know what will work for them and what won’t. Talking with youth about their priorities, fears, daily commitments and safe and unsafe places in the community helps shape the design of any service or activity. We also know that adolescents and youth value mentorship in the form of peers, role models and adults who can help them expand their horizon of what is possible and how to get there.

Our approach to youth unemployment focuses on three areas: training, job matching and business growth. We determine which methods to use based on the contexts and challenges within individual communities. In cases when we use all of these methods, we begin with training in technical and soft skills to build capacity and link young people to businesses and jobs, we then extend our programmes to promote the growth and success of these businesses.

Build long-term solutions with a holistic approach

By understanding the economic geography of the countries in which we work, we’re able to identify viable opportunities and create sustainable change, so improvements and job creation last beyond our involvement. A market assessment allows us to understand the needs of potential employers, so we can help ensure the skills young people are developing will match the needs of local economies.

A prime example of this is our work in Jordan, where young people make up 60% of the population and nearly 40% of them are unemployed. One of these young people, Laith, 23, was sporadically working agriculture and odd jobs to make ends meet. He was also growing increasingly discouraged about his future — until a Mercy Corps vocational training in solar panel installation empowered him with a new outlook.

“Not being employed is very difficult, hard and painful. It’s like being trapped in a closed well,” he says. “The training that I received … was like somebody casting some light on the well, and I can finally get out.”

In addition to training that’s relevant to Jordan’s local economy, Mercy Corps is generating opportunities that match the demand of job seekers, both in skill and quantity.

“We have been trying to focus a lot on economic development programmes, with a focus more on job creation,” says Khaleel Najjar, a senior project manager for Mercy Corps’ livelihoods programming. More jobs equal more chances for youth to earn income, contribute to their communities and build a better future, for themselves and their country.

Create opportunity through technology

In other parts of the world, we’re embracing technology to help young people in isolated locations and tough environments access skills training and new job opportunities. In the Middle East and Africa, our Youth Impact Labs identify and test creative, technology-enabled solutions to tackle global youth unemployment, accelerating job creation so every young person has the opportunity for dignified, purposeful work. And in Gaza, where 70% of young people are unemployed, our tech hub and co-working space, Gaza Sky Geeks, gives teams of students a place to pitch startup ideas to a panel of judges.

Build resilience and create cohesion

Research tells us that youth employment programming is often most effective when layered with other holistic interventions such as mentoring and transferable skills. That’s why we include life skills training in our programmes as well as sector-specific skills training. Together, these skills help build job seekers’ resilience to unpredictable job markets, allowing them to not only secure and retain a job, but cope with changes in an evolving working environment.

In areas of the world where tensions around access to opportunities can arise, we work alongside the community to create opportunities for young people. In Kenya, for example, high unemployment rates are discouraging. Just when youth are on the verge of adulthood, they become pessimistic about creating a productive future when they can’t find a job. So we engaged young people in communities around Kenya to create opportunities for themselves.

With young people and local mentors, Mercy Corps developed a system of youth bunges, the Swahili word for parliament. Through this bunge system, groups of 10-15 young people gather to identify the biggest challenges in their villages and towns – unemployment being one of the top four. “The input of the young people was to identify what they really wanted, what challenges they had or have, and look for solutions,” says Zipporah Maina, a member of Mercy Corps’ youth programme in Kenya.

Mercy Corps’ impact around the world

In 2019, we carried out 51 employment programmes in 32 countries, including 22 highly fragile countries. Together, our global team reached 215,000 young people.

Here are a few more examples of what Mercy Corps is doing around the world to address youth unemployment and help young people build better, brighter futures for themselves and their families.

Guatemala

In Guatemala, we are engaging youth at more than 28 schools to diminish violence in urban communities, providing more than 14,000 students with the opportunity to engage in cultural, educational and employment related activities.

Iraq

We are reaching more than 15,200 youth (57 percent girls) at our youth centers in Iraq, where they receive psychosocial support, educational opportunities focused on skill building, and access to internships and apprenticeships. Since June 2016, we have provided access to safe spaces, support and mentorship for more than 38,600 adolescents and youth (52 percent girls) across the country.

Kenya

We developed a reality TV show called “Don’t Lose the Plot,” focused on engaging more youth in farming as a business. The programme aired in 2017 in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania and reached more than 3.4 million viewers — more than 60 percent of whom were ages 18-34 and female. We also developed an interactive, web-based farm budgeting tool to accompany the show called Budget Mkononi, which enlisted over 5,000 users in the first two months and was the show’s most popular social media feature, becoming a top trending topic on Twitter in Kenya.

Nigeria

We’re empowering up to 253,700 girls with improved financial literacy education and career guidance across 536 junior and senior secondary schools in Kano State, Nigeria.

Tunisia

Since 2011, we’ve supported more than 71,780 Tunisians (ages 15-35 years old) in developing the skills they need to be more effective in their life and workplace.

Uganda

We’re empowering more than 8,600 girls near the border of Kenya and Uganda with life-skills education, financial literacy training and resources for raising livestock so they’re able to earn their own incomes, manage their own finances and provide food for their families.

West Bank and Gaza

We launched Gaza Sky Geeks – Gaza’s first startup accelerator, co-working hub and technology incubator, where more than 2,500 young people have learned to code, develop apps and start their own businesses. In the last two years, 100 people have ‘incubated’ their projects for markets across the Arab world.